Coming From and Into Silence - The Quiet of Mark Hollis and Talk Talk

Mark Hollis, 1990.

I spoke briefly last week about my ritual with vinyl - specifically Talk Talk’s Spirit of Eden (1988), lying on the floor, in a dark room, and listening attentively to the album from start to finish. So that left me thinking about Talk Talk and I’ve been revisiting their final two albums, as well as Mark Hollis’ self titled solo album from 1998 - released before he turned his back on the music industry in favour of his family.

In my listening, its made me realise what a potent effect Hollis’ music has on me, but also music since - the list of artists that cite Hollis’ work is lengthy. Anyone who has listened to Talk Talk would likely be familiar with their early albums, specifically their hits such as ‘It’s My Life’, ‘Talk Talk’, or ‘Life’s What You Make it’ - the latter of which has maybe one of the most iconic piano tones going, I could recognise the song within the first second alone. That surely speaks of the magnitude of Talk Talk as a synth-pop/new wave group. Strangely then, following the success of The Colour of Spring (1986), the band used their larger budge to take a new, experimental direction that left them with an album that was considered ‘unmarketable’ by their label, EMI. Admittedly, yes - it’s probably quite easy to assert that Spirit of Eden is in no way a commercial album.

This sudden change in direction was, for Hollis at least, not so much a reversal but an awaited opportunity to produce an album of music that he had always intended to make. Hollis’ interest in jazz greats such as Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Gil Heron, combined with impressionist composers like Debussy, and Ravel, led him to create an album built around minimalism. In Hollis’ own words: ‘The silence is above everything, I'd rather hear one note than I would two, and I would rather hear silence than I would hear one note.’ I think there is a definite relation to experimental composers such as John Cage here, specifically the capture of music as something that speaks out of silence and falls back into it. Silence then is the punctuation for sound to exist, and then not exist. Hollis’ minimalism seems to be getting at the ability for music to exist in a space with enough room to allow all other incidental sounds around it - the sounds of strings ringing out, or the bloom and dissipation of a singular note across the space it was recorded in.

Recording in the Dark

I was fortunate enough, during my studies in music production, to have spoken with Phill Brown following a lecture in 2024. He described the process of recording this sudden change in direction for Spirit of Eden. The album was captured over several months, the studio was submerged in darkness - lit only by an oil projector, and guest session musicians were led into the room and instructed to play as they felt whilst being fed guide tracks. The approach then was painterly, a continuous capture of performances that could then be cut and selected to build an album. I think consequently, the challenge was firstly to not lose one’s mind whilst being in space devoid of time or vision, and then subsequently how to piece together a series of unpredictable performances. Hollis’ intention here was to work from the ‘first response’ of the musicians, or rather the ways in which they would perform instinctively without any direction. I suppose then, each performance would have fed upon those that already existed - rather than being composed in advance to achieve a desired effect. It certainly takes some bravery to record so much and then be willing to discard all of it if needed.

The final result, from an engineering perspective is incredible - the album has a colossal dynamic range, much like a classical recording, that spans from intensely quiet to overwhelmingly loud. Brown’s work is an incredible feat (along with future albums he worked upon) but it really presents itself as an extreme example of recording - 8 months of recording, and assembling, all from endless overdubs and trying every idea possible.

I should add - the instrumentation for this album, and subsequent releases, was decided as being wholly acoustic. Hollis no longer saw a purpose for synthesised sound, partly because it had always been a compromise to afford timbres he could not acquire so early in Talk Talk’s career, but also because he felt there was no need to revisit a sonic territory he had already captured. I think there is great admiration to be had for Hollis’ decision to pursue his own vision, however intense, with no fear of the reception - whether by the fanbase or commercially.

Spirit of Eden, Side One: ‘The Rainbow’, ‘Eden’, and ‘Desire’

It might be worth listening to these tracks as you read - if you so wish. The first three tracks of Spirit of Eden form one singular movement, blending between one another. The opening of ‘The Rainbow’ alone spans about the duration of any prior singles Talk Talk released. From the moment the guitar line enters, followed by the harmonica, I feel as though my ears somehow ‘lean in’ to the album. It commands your attention. Importantly, the album establishes that it is about dynamic range, and pace, rather than tempo - these tracks are slow, yet not a single strike, or sustain of a note feels wasted. ‘The Rainbow’ transitions from serene, swelling woodwinds, to what resembles Whale Noises, and finally a cavernous guitar - all before a piercing harmonica announces the arrival of the rhythm section. Just as a pop song would be finishing, Hollis gets started with his vocals.

Importantly, Hollis’ vocals are no longer present for the purpose of a lyrical message, in fact it’s very easy to disregard the words. Instead, the lyrics - albeit still important - now function as a phonetic script to convert Hollis’ voice into its own instrument - to my ear, perhaps a trumpet. I should clarify too, I mean that in a complimentary sense, I think Hollis’ voice has a beautiful passion, defined by his nasal belts and quiet, fragile waver. On the topic of lyrics, they help inform Spirit of Eden as a strange combination of religious, pastoral topics draped over a backdrop of jazz mood music. Recurring themes include justice, guilt, sin, and redemption - all in ways that I feel are more present in the tone and sound than perhaps the lyrics themselves.

I wonder then, if the visual image of ‘The Rainbow’ can be read into the sonic landscape of the track. If so, around the 5:35 mark there is a sudden and unexpected flourish of timbres, that to me, functions as its own kaleidoscopic range of musical colours. It makes me think of Kandinsky’s paintings, and visual response to music from synaesthesia.

Towards the end of' ‘The Rainbow’, the soundscape is barren - unwelcoming, and devoid of the colours that populate the majority of the track. Hollis’ voice intimately whispers before two droning horns populate the left and right channels. It’s as though the composition clouds over, entering its own night, creating a bed of quiet uncertainty before ‘Eden’ arrives with its building, major stride. I find it easy to notice how easily I let the various sections of the tracks wash over me, whilst I may pay greater attention to others - it lulls my attention continuously. ‘Eden’ for example, is continuous in its use of crescendo, from a quietly strummed guitar growing in intensity until the amplifier begins to distort, expanding out into the formerly silent space it occupies. Coupled with this, the rising impassioned refrain of Hollis’ lyrics - in this case discernible and assertive: ‘everybody needs someone to live by’. Building into a firm climax before again falling into a more doubtful bed of introspective pads and layers. There is a continual coming and going of musical textures and sounds, that somehow don’t step on one another nor disappear from focus. It’s a very elegant demonstration of Hollis’ minimalism, of all the sounds and timbres that are each taking their turns to announce themselves, blossom, and then wilt back into the backdrop they came from - in this case, the space of the studio room. Around 5:30 there is a brief period of simmering cymbals, before the song decides to start up again, this time transitioning into dribbling, aleatoric piano notes.

Cue, the final part of side one - ‘Desire’. The track almost takes on a driving, blues-rock rhythm - driven by its evenly paced guitar part. The song builds, and Hollis’ vocals seem to take the strongest present they have yet on the album. I’ll admit the lyrics are quite unintelligible - at least I had to look at them, before they then made total sense. This song really seems to be the explosive accumulation of the prior tracks - pushing the dynamic range with exploding drums, guitars, and Hollis’ yelped cries. It’s a satisfying build of instruments that begins to organise itself into something that sounds closest to a band yet on the album. Credit is also due to the noble performances of both a shaker and cowbell, both as direct elements of the composition…

And of course, the epic sum of driving drums, hammond organ, and guitar is collapses in on itself - back into silence.

Side two offers more introspection and mood. ‘Inheritance’ opens, sailing on a continuous pulsing cymbal before finally growing into an unusual flurry of artful discordance (to save my lack of precise theoretical knowledge). ‘Wealth’ however is perhaps the quietest track of the album - as though you’re alone with Hollis as he appeals for his own salvation. I love the use of space in the composition, allowing Hollis’ voice to fade in and out over the clicking onset of the hammond organ’s notes.

Between these two lies ‘I Believe in You’, the chosen single (if you can call it that), of the album. It’s perhaps the most direct track on the album, being considered by Hollis as a humanitarian plea to his brother’s heroin addiction. It’s perhaps the most' organised track on the album because of its clear, discernible sections - especially the arrival of the bass guitar at 1:48. For me, it’s one of the standout moments of the album, it lifts the song so elegantly and elevates its beauty further.

Hollis’ lyrics become direct, carrying his hurt:

‘Tell me how I fear it

I buy prejudice for my health

Is it worth so much when you taste it?’

There is an underlying sense of forbidden temptation in the lyrics, perhaps keying into the album’s title. From these lyrics the song largely adopts the approach of mantra, with Hollis’ repeated appeals, allowing him to fade as the overall arrangement takes over. For me, the final fade of the Chelmsford Cathedral boys choir is maybe the closest the album gets to being a religious experience. It’s arranged to be reminiscent of a requiem, compounded by the loss of Hollis’ brother, Ed, who succumbed to his addiction around the album’s release.

Laughing Stock

Following Spirit of Eden, Laughing Stock came about as another of Hollis’ experimental creations - one that led to the band that was Talk Talk parting ways. Again, the album was largely considered unmarketable after Talk Talk switched label from EMI to Polydor. With Hollis’ vow to never repeat himself, the album doubled down in focus from Spirit of Eden, this time using even more limitation in its engineering and production. From my reading, it was captured using a Neumann binaural head, as well as other more unusual micing techniques - such as using contact microphones on the toms for a sound that was more textural than accurate - I suppose, impressionistic. I believe much of the time the instruments were recorded with single microphones, even complex sources such as drumkits. From this, the album was recorded with no compression, and the desk was left at maximum volume so that the dynamics would ‘behave’ themselves. In the end it’s reported that about 80% of the album was cut, with some musicians not even featuring in the final album.

Laughing Stock opens with a more sinister tone, ‘Myrrhman’ offers no piercing harmonica or waking light. In fact, the song sounds claustrophobic - from the beginning it’s apparent that the tremolo on Hollis’ amplifier (a Vox AC30) is acting upon its hum, drawing a sonic halo around the recording room. At the same time, the drums ‘set up’ in the background, a deliberate nod to Miles Davis’ ‘In a Sentimental Mood’. Once Hollis’ vocals enter, the unease grows, setting itself apart from the more pastoral opening of Spirit of Eden:

‘Place my chair at the backroom door

Help me up, I can’t wait anymore’

The imagery is dark - it seems like suicide, or otherwise, a spiritual appeal for help - or both. The lyrics have no discernible pattern of delivery, they come wavering and broken. Even the pause from ‘help me up’ helps convey the desperation of ‘I can’t wait anymore’. There is a need for silence, for pausing, to allow the ambience to breathe. This uneasy bleeding of sound into the space, and the double bass’ wandering plucks, builds the tension - all while remaining resistant to any kind of musical centre. Myrrhman is a track that never repeats itself - always moving to a new section with purpose.

The title itself - Myrrhman, suggests an appeal to Christ. It leaves me to speculate whether Hollis is purposefully introducing the track’s voice as an artist who is reaching out for a listening ear, or some form of redemption for a creative act. Even the album’s title, Laughing Stock, seems to hold potential as its own grim, sardonic reflection of either the band, the album, or their lack of commercial success from Spirit of Eden. Maybe then, a play on a literal ‘fall from [commercial] grace’.

In a way, it’s hard to notice that Myrrhman does in fact end - carried over again by the pulsing tremolo of the amp before being overtaken by a pulsing cymbal over a regulated drumbeat. I believe the drums here were recorded with a single microphone - I may be wrong, but they sound incredible, a testament to Lee Harris’ performance. Importantly, the microphone was recorded well away from the drumkit, allowing the cymbals to spill out and wash into the room’s ambience and of course softening the attack of the drums themselves. Hollis’ lyrics now deal with an acceptance of sin, seeking redemption through strident guitars and percussion - once again, the dynamic range of the album makes itself known. Where Myrrhman resisted repetition in its sections, Ascension Day shortens its verses by a few beats at a time, flipping the impression of where the downbeat lies. The ‘ascent’ of the song is spectacular too - a growing crescendo of guitar before an abrupt cut.

A Neumann KU 100 Binaural Microphone - If you’ve never experienced binaural audio, I recommend to seek out an example on YouTube. In this instance, they emulate the dimensions of a real human head and ears, and then place microphones within each ear cavity to record. The result is that when listening back on headphones, you gain the impression that you are in fact presence in the recorded space.

Enter ‘After the Flood’ - a song that creeps in quietly with its muttering piano and bird-like harmonium? In fairness - I am genuinely unsure as to what the instrument is. Phill Brown regards the drum recording on this track as the favourite sound of his (legendary) career. It was achieved by recording the drums around 28 feet away, once again allowing the drums to fill out the ambience of the live room. The issue therein came from the room’s climate, which fluctuated dependent on the air conditioning, and so introduced a variable delay of around 20-30 milliseconds. Such a delay was enough to disturb Lee Harris’ performance, putting him out of time whilst recording. To remedy this, the drum kit was close mic’d for the sake of monitoring only, with the kick drum being the only element to survive - just to fill the low end out. From this, the mic placed 28 feet away was delayed until it was in sync with the rhythm of the track. Another unique timbre found on the track is the Variophon solo at around the 4 minute mark, one which… well … played itself. The instrument malfunctioned, whilst recording, prompting a sustained series of fluctuating notes and internal feedback.

New Grass is another track to showcase Lee Harris’ drums, with a simple continuous swung groove accompanied with delicate, spacious guitar parts. The drums themselves were deemed so good that Unkle sampled them for use on their track ‘A Rabbit in Your Headlights’, a track with a completely different tone but that is also worth its merits. I think this might be where the heavens open up on Laughing Stock, as Hollis sings with more optimism in his lyrics. I am particularly fond of his own tremolo-like vocals at 4:54, wavering over a flurry of strings. It’s a very brief but beautiful moment that I feel could not be captured the same way twice. Around 6:40 the tracks’ upbeat energy turns back to melancholy, where solemn piano chords carry the song back into a discordant string section. Once again, the listener finds themselves in an ambiguous, uneasy tonality, but one that is less intense than Myrrhman. Finally, a guitar stands above, issuing a solo that feels as though it should explode and flourish at any point, but which instead falls back in on itself - ruminating on a single note until fade.

The final track Runeii, seems to offer a final redemption for the character of Myrrhman. Again, like with Wealth, there is an introspective, consoling tone of voice found through Hollis. The vocals repeat over a series of spacious guitars and piano lines, left floating without any drum for percussion.

Anechoic Chamber Music - Mark Hollis (1998)

I write this title because I saw it on YouTube, under a playlist name and it brought me great amusement. The idea that chamber music, a type of composition whose identity is intrinsic to being performed in a space, could then be coupled with a space that eats reflected sound is just quite amusing. Still, it’s worth thinking about. Following Talk Talk’s split, Mark Hollis composed more music - now with the advantage of his personal computer, to compose a new series of songs that would comprise a new album. This led to his only solo release, the self titled Mark Hollis (1998), an album that he intended to release under the Talk Talk name before realising no members of Talk Talk played upon it, except for himself. It’s a beautiful, introspective album - more so than the last two Talk Talk albums. I only discovered it three years ago, long after listening to Spirit of Eden and Laughing Stock.

So is it chamber music in an anechoic chamber? I'm not sure. It’s interesting to think that Hollis was late to realise it was a solo album, or rather that it was not an immediate decision. I suppose that covers the anechoic element - is it an album that asks for a listener? I’m not entirely sure. The album goes further down the rabbit hole of minimalism, paring back the instrumentation in a lot of places. It was recorded with two microphones, placed in fixed positions - either side of the room, and then performers were placed in the room via marked positions on the floor. Again the dynamic range is colossal, and evident from the sheer volume of tape hiss. The album was recorded with the intention of playback representing the instruments as they would be in the space - if you turn the volume up too loud, the hiss becomes very apparent. In its own way though, I think that adds its own texture, or ambience - perhaps the same way that film grain suggests something organic, or sharper? Performances were also singular, often achieved in one take (there is seemingly a false start at the beginning of The Watershed).

The opening track, The Colour of Spring, references a previous Talk Talk album. ‘Forget our fate’ sings Hollis, over a piano. Again, Hollis is in a state of appeal - the tone is resigned, somber. If Spirit of Eden was the party, and maybe Laughing Stock was the afterparty… then is Mark Hollis the late night once everyone has gone home? I’m not sure.

This song features ones of the most beautiful piano lines I've heard. From the opening there is a strong sense of a major feel to lead the song, ushering in the vocals promptly. Really, with the absence of any other instrumentation, the track becomes a sort of intimate, impassioned prayer. From the lyrics I wonder if Hollis is disregarding fame or wealth for the importance of his musical achievements. The standout moment, at least for me - is with the arrival of this aforementioned piano line - at 2 minutes. It’s a descending section that’s somewhat reminiscent of Sting’s ‘Mercury Falling’ in a way. It’s a series of seventh chords, starting with a descending section of ‘brighter’ (accentuating higher pitches) chords which then invert into a series of ascending, but more dissonant chords - darker if you will. It feels as though the chords themselves become fallen, like an angel from the sky, before passing through the ground and emerging into the underworld. Is that a dramatic interpretation? Maybe. I enjoy the way the tape hiss seems to become more prominent in the ‘darker’ section, presumably to maintain a consistent level for the lower pitched chords. I’m sure there is someone who could very quickly voice what I'm discussing with precise music theory, but I don’t have that to hand - in a way, I’m glad. In this case I think my ignorance allows me to focus my response in a way that’s emotional. It’s really just a piano, some reeds, and Hollis’ voice, all calling out into the live room.

Seamlessly, the piano is replaced by a guitar, ushering in ‘The Watershed’. This is one of the more energetic tracks on the album, alongside ‘The Gift’, both of which reveal Hollis leaning even further into a jazz influence on the album.

My attention however, is drawn to the emotional centrepiece of the album: ‘A Life (1895 - 1915)’. It’s a song which functions as a form of elegy for the life of Roland Leighton, a soldier poet. It’s not a conventional topic, or at least not what might be expected to follow from other tracks - especially with the more abstract religious elements of Spirit of Eden, or Laughing Stock. Given its location in real history, it takes a more humanitarian focus. I believe Hollis’ interest was in the experiences of Leighton’s twenty years - being born at the turn of the century, the patriotism and then the fast disillusionment that emerged from World War One. Lyrically, there is nearly nothing to portray this - the title perhaps carries the most meaning. The lyrics are fragmented, painting images - simply ‘uniform’ or ‘avow’, ‘relent’ and ‘such suffering’. Instead, the music carries forward the feeling and confusion of the piece.

From its opening, a series of freeform clarinets discord over one another, issuing uncertainty before adopting a shared phrase, over and over. Eventually the instruments begin to harmonise, solemnly, and once again with rising tape hiss. An atmosphere emerges, and Hollis’ lyrics make their appearance. The single line phrases now make sense, as Hollis sings into the song’s space, with great anxiety and despondency. Finally, there is a brief section of shaker, imparting the song’s new rhythm, before piano and guitar adopt the left and right channels. Centrally, female vocals begin to swirl in the space - singing lyrics that are indiscernible, confused. It’s only by 5 minutes that the track seems to have reached its confused conclusion - migrating once again into a more freeform section. Just as the track fades, Hollis can be heard faintly singing ‘Here I lay, here my Lord’, adopting the passing of Leighton’s person.

I find the track disturbing - it’s not an easy listen, nor is it particularly comprehensible. That might be a failing on my part - it’s not criticism either, I believe it just resists interpretation. This is perhaps where the album really does take on a quality of being ‘anechoic’, of not caring for its listener. I find it disturbing to contemplate the life and suffering, confusion even, of someone who existed in a period of such radical change, and who lived for less time than I have already. When overlaid across this musical backdrop, I do find it emotive, but I can’t pin down why. The song deals with a life that was shortened by war, and re-enacts it within its own minimalist composition - one that obliquely references its subject matter. Maybe then, that is inconsequential and to look for a meaning is secondary to the affect of the composition. The transition from the opening to midsection is elegant and beautiful. It’s the brief pause, silence, that enables the elegiac tone of the track to emerge, a movement from the discordant woodwind into the more secure yet mournful piano.

I definitely appreciate the more humanitarian focus on this album, specifically Hollis’ engagement with individuals who suffer or encounter redemption. I just wonder if there is a set way to engage with it or if the sense of ‘mood’ is instead integral to the experience. That then could be what I find so alluring about Hollis’ music. Somehow, he quietly weaves great emotional depth into his music. A sort of musical sleight of hand - whether that be his whispered vocals, barely breathing into a space, or his impassioned yells.

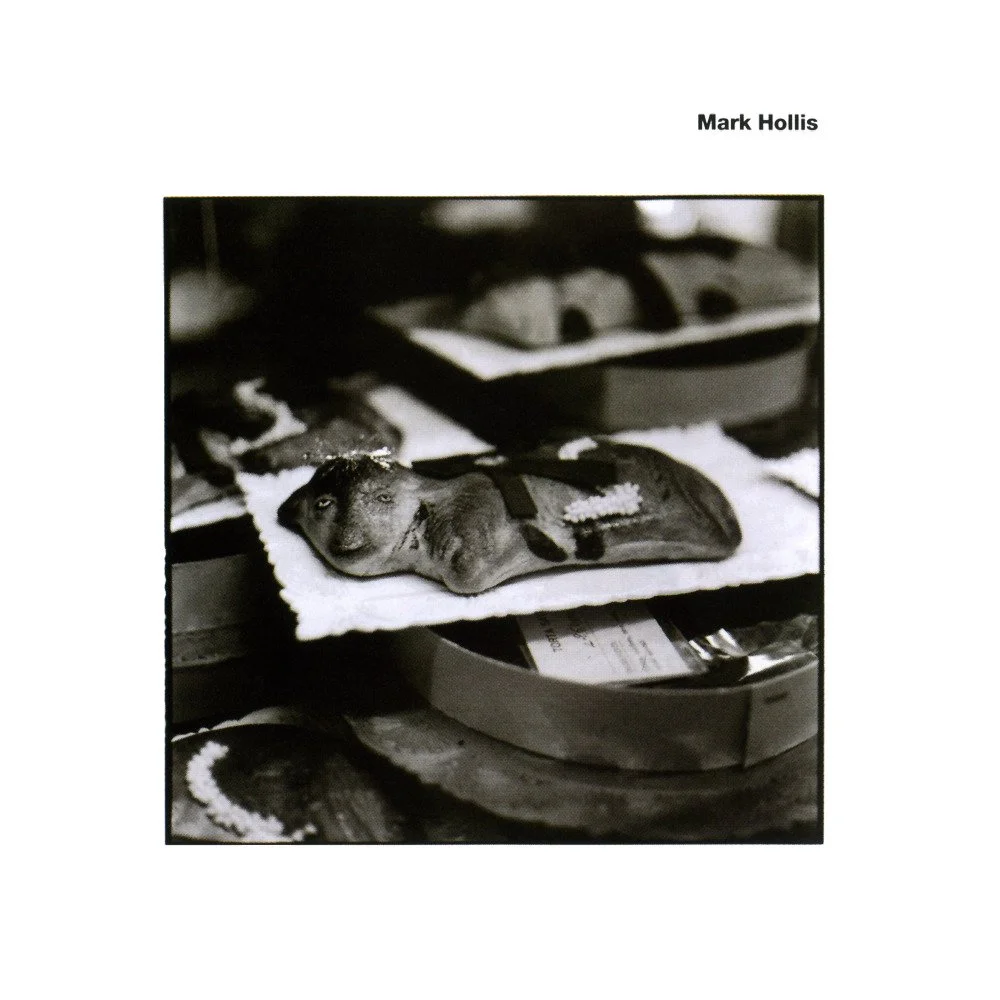

The album artwork for Mark Hollis (1998)

The album’s artwork is also complicit in resisting interpretation. It depicts an Easter bread, from Italy, depicting the lamb of god. It’s quite a bizarre cover image - the focus on the face of the image, slightly deflated, and then attached to a formless body is somewhat disturbing. Couple that with the scale that becomes apparent from the surrounding context and you’re left visually puzzled. Hollis stated about the cover: ‘I like the way something appears to come out of his head; it makes me think of a fountain of ideas. Also the manner how the eyes are positioned fascinates me. When I saw the picture for the first time I had to laugh, but there’s something very tragic about it at the same time.’ I’m inclined to agree, I suppose once you realise it’s bread then it’s easier to laugh, but you find yourself double checking as you see a form of humanity in it - at least in the face. There’s a weariness to the deflated expression. Disturbance aside, I wonder if that is a lens with which to view Hollis’ album, specifically the habit of meaning and instruments emerging quietly, becoming loud, and fading once again. I often feel the effect is there to grasp, but then gone just as you catch a glimpse - perhaps a similar confusion to first viewing this image.

The final track I’d like to discuss is ‘Westward Bound’. Hollis is quite autobiographical here, referencing his wife, and then his sons - the reason he turned away from music. I find the song to be quite intensely emotional but I can’t pin down why. Maybe it’s the delicacy of the vocal sitting right in your ears, or the melancholic interaction between the bass and guitar. The energy of the track feels worn, but steadfast. There’s a lyrical movement - first a discussion of love and family, through to self-burden: ‘ the world upon my back’, moving from those two elements to a bucolic vision of the ‘threshing line’. It makes me wonder if the triplets of ‘Mute I walk, Idle ground, Westward bound’, is Hollis quietly bowing out over a pastoral landscape. It’s his own desire to resist music and spend time with his family.

I remember hearing of Hollis’ passing, in 2019, and being greatly saddened by it - not because I had an expectation for there ever to be another Talk Talk album, but that the great ideas carried out by his voice had essentially gone out. In one of his few interviews, in 1998, Hollis mentions timelessness as being key to his musical philosophy: ‘the ideal is that the album won’t be recognisable as having come from any time, having been recorded in any particular year. And the fact you’re working with acoustics, helps, means you can’t date.’ I think this really is present on Mark Hollis, it’s an album that does resist direct interpretation. Does it exist in its own anechoic chamber? Perhaps so - I’m not sure it’s an album that could be reproduced, let alone imitated. Any influence it could give would have to be oblique too.

I think Spirit of Eden and Laughing Stock are timeless too, but there is something deliberate about Mark Hollis - for better or worse. The final song features two minutes of silence - a long fade of tape hiss, into nothing. It feels as though it’s the ultimate achievement of Hollis’ vision when he first set out to create Spirit of Eden. It’s the rising of music, from nothing, and back into nothing. The final track could cut so much sooner but it doesn’t, there is a choice for the space to fade slowly and quietly - an invitation for the reflection - both personal, and in a literal sense… the sound itself. Is silence a sad thing? I’m not sure. It permeates, and punctuates all recordings - it’s the necessary antithesis to the life of sound I suppose.